SVIT Switzerland writes on its website about the debate on the Federal Housing Office’s rent model from the 1980s: ‘Shortly before Christmas, the Federal Housing Office published the commissioned study «Überprüfung des Mietzinsmodells des Bundesamtes für Wohnungswesen». In it, the authors from IAZI AG come to the conclusion that the rent model from the 1980s is no longer up to date in several respects.’ And further: ‘Various assumptions in the study must be rejected; the authors’ main demand for a standardised new model cannot be followed.’

The BWO rent model assumes that 70% of rental income from investment properties is used by the owner to cover capital costs. The remaining 30% is allocated to all other property costs (e.g. maintenance and operating costs). The capital costs in turn were divided into 60% debt and 40% equity costs.

A new rent model should underpin the changes to the VMWG

The author of the article in ‘Immobilia’ writes in the introduction that the initial situation is well known. Federal Councillor Guy Parmelin feels compelled to deliver on the issue of rent control. His initiatives in this regard have come to nothing due to the hardened fronts. And the ‘housing shortage action plan’, which was announced with much fanfare, understandably did not deliver any quick results either. The latest study comes at just the right time, especially as an amendment to the Ordinance on the Rent and Lease of Residential and Commercial Premises (VMWG) is in preparation. The rent model is now apparently to be revised in the same go and underpin changes to the VMWG.

Rental model no longer up to date according to IAZI study

According to the IAZI, the share of ‘other property costs’ differs from the assumptions in the BWO model. According to their study, the ‘other property costs’ are below the assumed 30%, regardless of owner type, building age, building size and observation period (2005 to 2023). For institutional owners, the study gives a value of 20 to 22%. For private owners, the figure is around 24 to 25%. The study also concludes that the financing of properties owned by institutional owners – private owners are not analysed in this regard – does not consist of debt and equity in a ratio of 60 to 40, but rather in a ratio of around 20 to 80 for investment funds and 10 to 90 for investment foundations. For real estate companies, the ratio is 50 to 50.

Study aims to take legal and political action with an economic model

However, the author Ivo Cathomen, Dr oec. HSG, publisher of the magazine Immobilia and deputy managing director of SVIT Switzerland, points out a sore point in his article when he writes: ‘As the authors rightly state in the introduction, the rent model is an economic model. However, they turn it into a legal or, as a consequence, even a political model by not basing the calculation of other costs on economic criteria but on the case law of the Federal Supreme Court. For example, the authors leave out provisions for future maintenance costs and extensive overhauls as well as amortisation for legal reasons, although these are necessary or even mandatory from an economic point of view. Provisions and amortisation would smooth out the costs over the periods and provide a more realistic economic picture.’

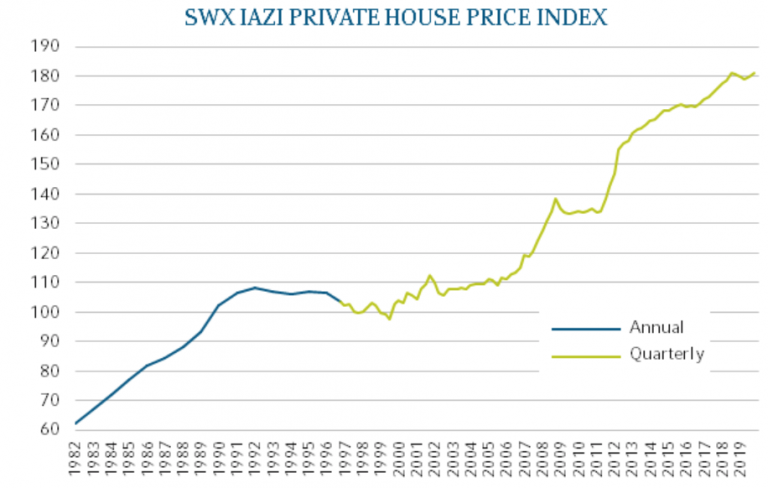

It may well be, writes Cathomen in his article, that the effective cost blocks have shifted over time, in particular due to interest rate trends. However, the fact that entire – and significant – recurring cost blocks should be disregarded from the point of view of continuity raises questions from an economic perspective. After all, according to an SVIT article by tenancy law expert Beat Rohrer, the provisions and amortisation amount to 10% of the gross rent.

Study based on incorrect or missing data

Cathomen also questions whether the target rents should actually be used in an economic model or rather the effective rents. The rent model does not take into account the remuneration costs, writes Cathomen, which are nevertheless incurred by institutional investors. According to the study, these remuneration costs range from 5% (investment foundations) to 15% (property funds and companies) of the target rent. As mentioned, the study also fails to take into account the financing of properties owned by private owners. The ratio of borrowed capital to equity of 60 to 40% is still likely to apply to these properties. Finally, the study insinuates that the owners would achieve a high or too high return on equity from property investments. The results of the study only stated that due to the high equity ratio of institutional owners, a higher proportion of rental income is attributable to the return on risk-bearing capital.

SVIT cannot follow the conclusions of the study

However, Cathomen believes that the authors’ conclusions in the study are extremely disputable. According to the study, ‘the rental model should be designed as independently as possible of ownership and the financing structure’. Cathomen does not share this conclusion. The growing disparity in ownership and financing structures stands in the way of levelling. Such a levelling would presumably result in considerable disadvantages for one or other group of owners.

Read the full article in the advance copy of the January issue of Immobilia.