Plastic shapes our everyday lives like no other material: from packaging to trainers, from household appliances to furniture, from cars to architecture. For decades, plastics stood for carefree consumption and revolutionary innovations, they inspired the imagination of designers and architects. But these times are over, since the consequences of the plastics boom have become drastically visible.

The Ocean Cleanup, crew sorting plastic on deck after waste salvage by System 002, October 2021, © The Ocean Cleanup

With the major exhibition “Plastics. Remaking Our World”, the Vitra Design Museum is examining the history, present and future of a controversial material until 4 September 2022: from the rapid rise of plastics in the 20th century to their devastating consequences for the environment and solutions for a more sustainable approach to plastic. On display will be rarities from the early modern era, objects from the pop era, but also numerous current designs and projects, including pragmatic innovations, initiatives to clean up the oceans, concepts for recycling, and bioplastics based on algae or fungal cells.

Marco Cagnoni, Plastic Culture / Vertical Bioplastic Farm, 2018; Photo: Nicole Marnati

To kick off the exhibition, a large-format film installation illustrates the conflicts that arise from the production and use of plastic. Timeless scenes of pristine nature are juxtaposed with films on the production of plastics over the last 100 years, which highlight the lure of ever faster-paced and cheaper industrial production. It took over 200 million years for the fossil raw materials coal and petroleum, which form the basis of all synthetic plastics, to emerge, but in little more than a century they have become one of the biggest global environmental problems of our time.

Installation view “Plastic. Remaking Our World” © Vitra Design Museum; Photo: Bettina Matthiessen

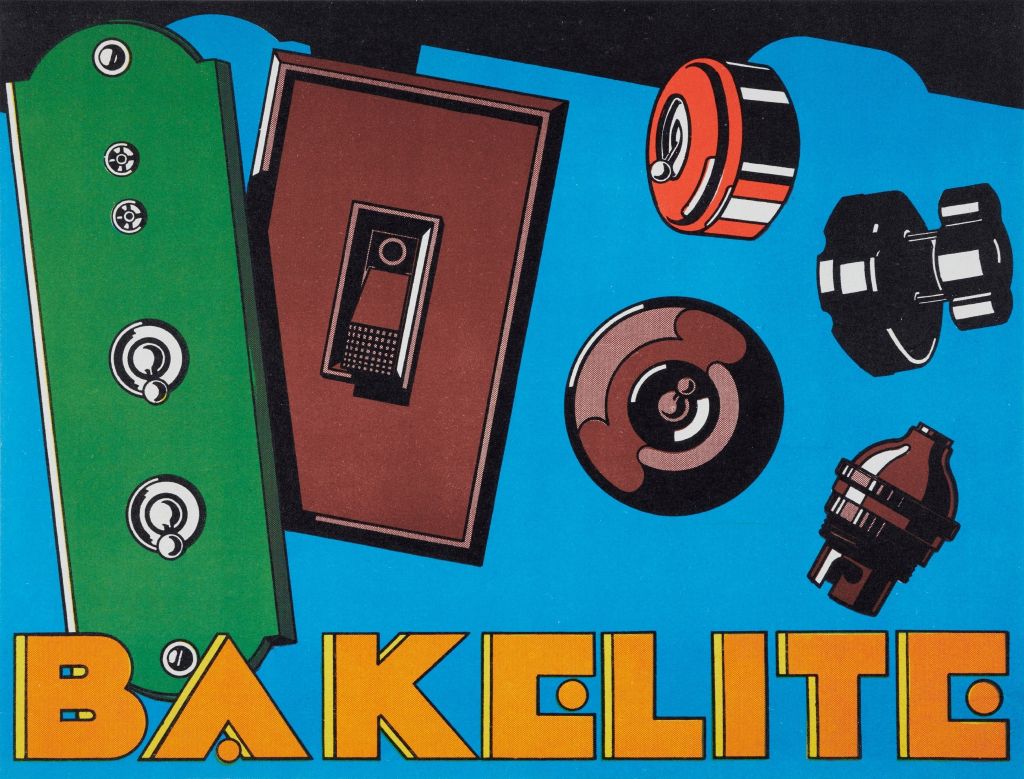

In the further course of the exhibition, the focus is on the development of plastics and their perception – from the beginnings in the middle of the 19th century to today’s global ubiquity of plastics. The first precursors were based on plant and animal raw materials: for example, horn and tortoise shell were used for centuries to design drinking vessels or cutlery. Gutta-percha, on the other hand, which was once used for decorative objects and sea cable insulation, consists of the thickened sap of the tree of the same name. When John Wesley Hyatt invented celluloid in the 1860s, he was looking for a new material for billiard balls, which were then still made of ivory. The first fully synthetic plastic was invented by Leo Baekeland in 1907. It was called Bakelite and was soon regarded as a material of unlimited possibilities. Because of its good insulating properties, Bakelite was used for light switches, sockets and radios and played a central role in the widespread electrification.

Bakelite advertising leaflet, 1930s; Courtesy Amsterdam Bakelite Collection

Today, plastic is ubiquitous all over the world and it is hard to imagine everyday life without it. This is especially true in the health sector, where the positive, sometimes life-saving properties of plastic are just as evident as its negative, even life-threatening effects. The consequences of the plastic boom have burned themselves into our collective consciousness: from microplastics in the soil, in the oceans and in our bodies to mountains of packaging waste, most of which is still disposed of or incinerated today – with immense ecological consequences on a global scale.

Installation view “Plastic. Remaking Our World” © Vitra Design Museum; Photo: Bettina Matthiessen

A separate exhibition area in the Vitra Design Museum Gallery is dedicated to the topic of recycling. Here, visitors can learn about recycling cycles in an interactively designed room and experience how valuable and inspiring recycled plastic can be as a new raw material through the “Precious Plastic” project (since 2013) by Dutch designer Dave Hakkens. The FlipFlopi project in Kenya shows that design can raise awareness and push for important changes in legislation. A traditional sailing ship, a Dau, was built from recycled plastic and now sails around as a mobile information centre on the topic of plastic waste.

The Flipflopi is a traditional sailing ship, a Dau, made of recycled plastic. Courtesy The Flipflopi

Overall, the exhibition “Plastic. Rethinking the World” paints a critical but also differentiated picture of plastic as a material. Interviews with designers, scientists and activists conducted especially for the exhibition show how important the joint efforts of politics, industry and research are in solving the plastic problem. But even if everyone gets personally involved, there will be no simple one-size-fits-all solution. It is therefore particularly important to illustrate the complex interrelationships and to ask: How did we become dependent on plastics? Where is plastic essential and where can it be reduced or replaced? And finally: How can we use plastics more intelligently and sustainably in the future?

Also on the subject of plastic, the online magazine COLOSSAL recently published an article showing how artistic sculptures can be created from plastic waste. You can find an example here.

Teaser image: Richard John Seymour, from the series “Yiwu Commodity City”, 2015, © Richard John Seymour